![With this completed, Lieutenant George Gilmer left Fort Daniel (Hog Mountain in present-day Gwinnett County), traveled south on Peachtree Road and completed Fort Peachtree [Gilmer] on a small knob overlooking the Chattahoochee. At the time the fort was built this was the western edge of America's frontier and not a part of the state of Georgia.](AtlantaHistory_files/shapeimage_5.png)

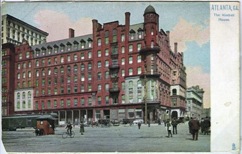

Kimball House -- Postcard

"The Kimball House. The original Kimball House was burned in 1885, and the present structure, covering almost an entire block, completed in 1894. The hotel, seven stories high, is the political headquarters of Georgia, is first-class and modern in every respect and contains 440 rooms. Ex-President Cleveland was entertained here in 1887, and many other distinguished guests have honored the hotel with their presence."

"The Kimball House. The original Kimball House was burned in 1885, and the present structure, covering almost an entire block, completed in 1894. The hotel, seven stories high, is the political headquarters of Georgia, is first-class and modern in every respect and contains 440 rooms. Ex-President Cleveland was entertained here in 1887, and many other distinguished guests have honored the hotel with their presence."

Peachtree Street Viaduct

1942 Post Card

Peachtree Street

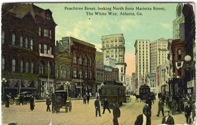

Peachtree St. looking N. from Marietta St.

The White Way Atlanta Ga.

Peachtree Street and Broad Street

Great White Way

Atlanta Ga.

Marietta Street Looking West

Birds Eye View of Atlanta’s Business Center 1916

Whitehall & Marietta St. 1905

Piedmont Driving Club

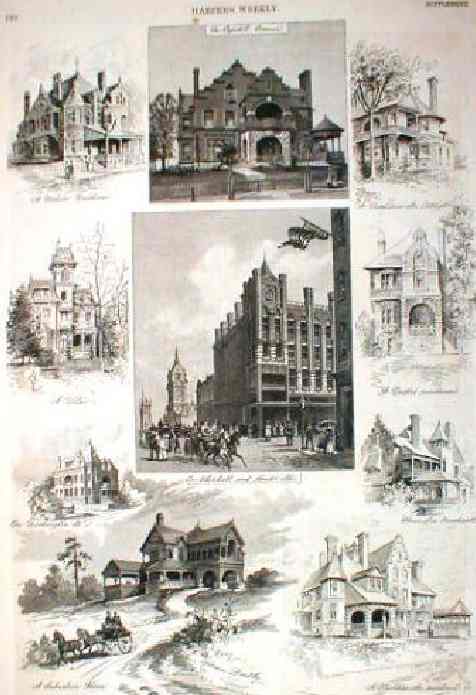

Harpers Weekly

Shown: Modern Residence, Capitol Avenue,

Peachtree St. Cottage, A Villa,

Doctor’s Residence, Washington St. Merchant’s House,

Suburban Home, Corner of Whitehall & Hunter St.

Peachtree & Broad Streets

Georgian Terrace and

Ponce de Leon Apartments

1938 Post Card

Colonial Terrace Hotel

2140 Peachtree Road N.W.

Atlanta’s Only Resort Hotel

Open All Year ‘Round

Postcard 1907

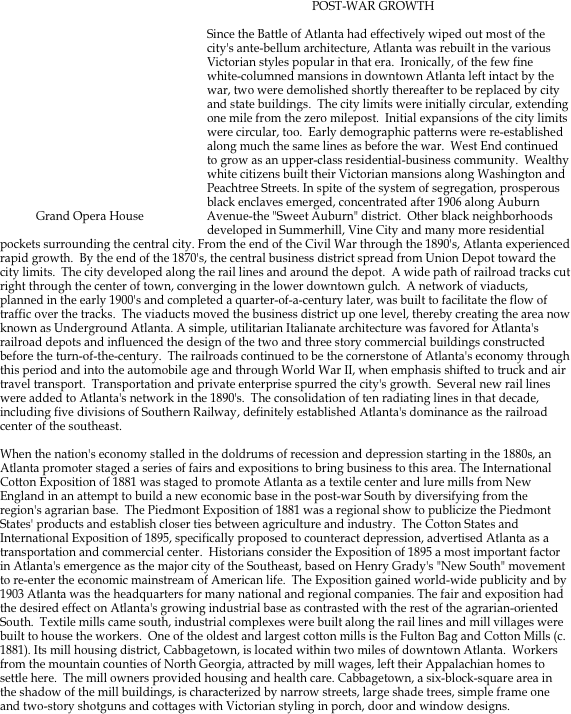

Left - This antiquated looking old structure, which is standing today in an out of the way on Trinity Ave. not far from Trinity Methodist Church, where if receives scant attention at the hands of the passerby, is the first two story frame building ever erected in Atlanta. No special effort has been made to preserve it, but some mysterious providence has kept it from disappearing, and even amid the ravages of civil war when the city itself was destroyed by the torch and nearly every building burned to the ground, it managed to survive.

Dating back to 1836, it was erected by the owners of the Western & Atlantic Railroad when this place, which was then an almost uninhabited wilderness, was first chosen as the terminal point of the line, and it was used as the headquarters of the company while work of constructing the line was in progress. Ex - Chief Justice Logan E. Bleckly once kept books for the company in this building and religious services were frequently held upstairs by visiting ministers who came to the frontier settlement for the purpose of preaching to the future history makers of Atlanta. Originally the building stood on the site of what is now the Brown block near the Union passenger depot, but it was subsequently moved to where it now stands.

( this was written in 1902)