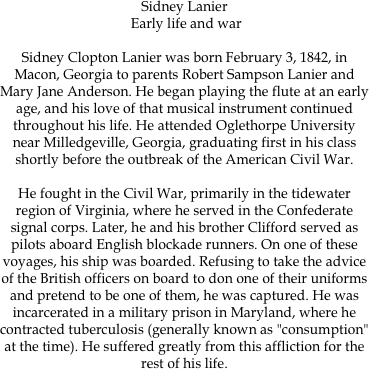

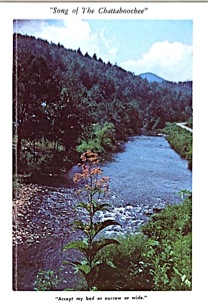

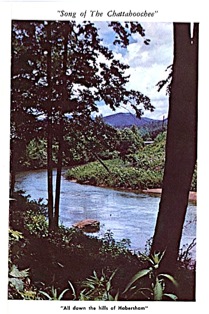

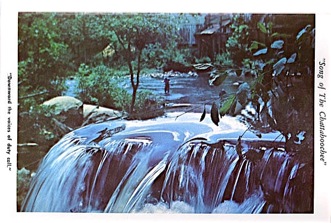

Song of the Chattahoochee

By Sidney Lanier in 1877

Out of the hills of Habersham,

Down the valleys of Hall,

I hurry amain to reach the plain,

Run the rapid and leap the fall,

Split at the rock and together again,

Accept my bed, or narrow or wide,

And flee from folly on every side

With a lover's pain to attain the plain

Far from the hills of Habersham,

Far from the valleys of Hall.

All down the hills of Habersham,

All through the valleys of Hall,

The rushes cried Abide, abide,

The willful water weeds held me thrall,

The laving laurel turned my tide,

The ferns and the fondling grass said Stay,

The dewberry dipped for to work delay,

And the little reeds sighed Abide, abide,

Here in the hills of Habersham,

Here in the valleys of Hall.

High o'er the hills of Habersham,

Veiling the valleys of Hall,

The hickory told me manifold

Fair tales of shade, the poplar tall

Wrought me her shadowy self to hold,

The chestnut, the oak, the walnut, the pine,

Overleaning with flickering meaning and sign,

Said, Pass not, so cold, these manifold

Deep shades of the hills of Habersham,

These glades in the valleys of Hall.

And oft in the hills of Habersham,

And oft in the valleys of Hall,

The white quartz shone,

and the smooth brook-stone

Did bar me of passage with friendly brawl,

And many a luminous jewel lone

-Crystals clear or a-cloud with mist,

Ruby, garnet, and amethyst-

Made lures with the lights of streaming stone

In the clefts of the hills of Habersham,

In the beds of the valleys of Hall.

But oh, not the hills of Habersham,

And oh, not the valleys of Hall

Avail: I am fain for to water the plain.

Downward the voices of Duty call-

Downward, to toil and be mixed with the main

The dry fields burn, and the mills are to turn,

And a myriad flowers mortally yearn,

And the lordly main from beyond the plain

Calls o'er the hills of Habersham,

Calls through the valleys of Hall.

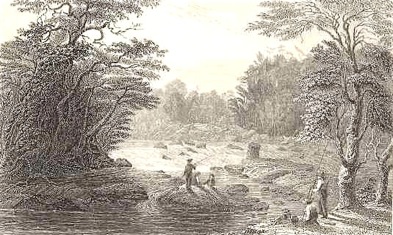

Along the Chattahoochee River, north of the original city of Columbus, a series of hills climax in a high bluff; Lover’s Leap. This beautiful area has always attracted visitors. Native Americans certainly used this riverbank to manufacture tools, to hunt and, especially, to fish, even thought the major historic period Indian population centers (Coweta & Cusseta) were located south of the fall line, archaeologists found a “flint quarry” in the approximate area, and a spud or ceremonial axe head in the McKnight Collection in

St. Louis museum is cited as being from Bibb City. Some residents insist that there is an Indian burial ground in the area, probably to the north of Bibb City. Indian legends form an important part of the local mythology. The most lasting is that association with Lover’s Leap, the rock bluff over the turbulent Chattahoochee. A frontier (or perhaps a high place) legend attributed the name of the pinnacle to Indian lovers who plunged to their deaths rather than live apart. While the Indians used this land, they probably did little to change the landscape.. The Europeans and Africans would transform the land in the 1850’s. John Winter, an important antebellum entrepreneur who also served as mayor of Columbus, harnessed a small portion of the river between an island (now in Bibb pond) and the Alabama shore. A small dam there powered his Rock Island Paper Mill, which also used water, from up river. Union troops destroyed this facility in 1865, and it was never rebuilt. This site is in the extreme northwest corner of the boundaries of Bibb City. The engraving above was printed in 1838. Overall the print size is 5 1/2”X71/2”