On a trip south, America's Scenic City seized The General in 1967. For 3 years a legal battle was waged over a locomotive & would be carried all the way to the Supreme Court, who refused to hear the case. It let stand a lower court ruling that the L&N RR owned The General & can dispose of it as they wished.

The state of GA had long desired The General, & had made it well known to the Louisville & Nashville RR. With the help of Gov. Jimmy Carter The General returned to the most appropriate place, in a cotton gin about 100 yards from the site of the original theft of the engine in Kennesaw (GA). Since 4/12/1972, The General has spent her retirement in the perfect place, the Kennesaw Civil War Museum, formerly the Big Shanty Museum, protected from the elements not far from the start of America's famous train story.

1870 Kennesaw Depot

1862 Locomotive chase now at Kennesaw museum

By MARK DAVIS

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Published on: 01/10/08

They caged and abused him. Days turned into weeks, the

weeks became months, and still he wouldn't talk. After all,

this was war, and he was a soldier.

When the government finally negotiated his release, he

returned a hero, but a modest one. First Lt. Jacob Parrott

went back to the fighting.

The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History.

First Lt. Jacob Parrott

A story from today's headlines? No, he endured prison's indignities nearly 150 years ago. And this soldier's war took

place on native soil, not some distant point on the globe. Now, Parrott is a star at the Southern Museum of Civil War

and Locomotive History. The Kennesaw museum recently acquired a carte de visite (literally, a visiting, or calling, card)

of Parrott, the first recipient of the Medal of Honor for his role in what became known as the Great Locomotive Chase. The 1862 pursuit pitted steam engines in a race from Kennesaw toward Chattanooga.

As wide as a playing card and only slightly taller, the carte features the black-and-white image of a young man. He is movie-star handsome, dark-haired, with a small mustache. His eyes are fixed on a distant point — a gaze acquired, perhaps, while looking through the bars of his cell? He wears a first lieutenant's coat bearing the insignia of the 33rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

Ava Wilkey, the museum's registrar and curator, can hardly keep from smiling at the image. She negotiated the card's acquisition, her first for the organization. It went on display in late December.

"It [the card] helps interpret national history," said Wilkey, who persuaded the museum's board of directors to buy the card for an undisclosed sum. "To have that here in Kennesaw is phenomenal to me."

It started at Big Shanty

Big Shanty

The 90-mile chase remains a phenomenon, the subject of

books and a 1956 film. It was a contest pitting men and

machinery that presaged the fast-moving battles of a world

war 50 years in the future. It began April 12, 1862, at Big

Shanty, a little whistle-stop now called Kennesaw. Led by

Union spy James Andrews, 19 other volunteers, including

Parrott, hijacked the General, its tender and three boxcars.

They planned to go as far as Chattanooga, destroying

telegraph lines and bridges, hoping to break the

Confederacy's communications and supply lines to bring a

quick end to the war.

The raiders moved quickly while the train's crew ate

breakfast at a nearby hotel. As the stunned crew watched,

the engine huffed away. Three railroad employees saw the

General gathering steam and ran after it. The race was on.

The trio ran two miles until they reached a hand-operated rail cart. They jumped on that and churned north, pushing the cart with a pole. When they crossed the Etowah River the men abandoned the cart for the Yonah, an old steam engine. The men in the General, meanwhile, did not know that the Yonah was behind them. They got delayed by other train traffic, allowing the older engine to gain ground.

At Kingston, the three ditched the Yonah for the newer, faster locomotive William R. Smith, but got stopped four miles later when they came upon tracks the raiders destroyed in their wheeled sprint toward Tennessee. Two hopped out and started running again.

Three miles later, they came upon the Texas, heading south through Adairsville. They disconnected its cars and resumed the chase, the Texas hurtling along in reverse, gaining on the General. By then, the men in the General knew they had not shaken their pursuers.

Resaca, Dalton: twin plumes of smoke, one hard behind the other, smudged the air. The raiders dropped timbers in their steel wake, hoping to slow the Texas, but it didn't work. They tried setting fire to a covered bridge, but a recent rain left it too wet to burn.

The race ended about two miles north of Ringgold, when the General ran out of water and could not make steam. The raiders fled into the woods. Confederate forces captured them within two weeks.

In the aftermath, Andrews and seven others were hanged. The remaining raiders languished in jail until the U.S. and Confederate governments worked out a prisoner exchange.

Honored for heroism.

The heroism of some of the captured Union soldiers

impressed War Secretary Edwin Stanton. He was especially

inspired by a dark-haired 20-year-old from Ohio who refused

to divulge any secrets to his captors. On March 25, 1863,

Parrott became the first recipient of the highest award the

nation bestows on its warriors.

Parrott returned to war and survived the bloodletting. He

went home to Ohio and made a living as a cabinet maker.

He died in 1908.

1947 Kennesaw Depot

He also had some cards made that featured his likeness. Last year, one caught the eye of a Massachusetts collector of Americana. Rex Stark, who has been buying and selling historical items for Stark didn't hesitate.

He listed it in a quarterly catalog he mails to collectors all over the country. One landed in the mailbox of an Atlanta Americana enthusiast, who told Wilkey about the Parrott card. Like Stark, Wilkey didn't hesitate. She called him.

Wilkey also prepared a proposal for the museum's board. The board agreed and the carte arrived by registered mail in October. It went on display a week before Christmas.

Wilkey plans to exhibit it for no more than six months, as the carte could become damaged in the light. She'll replace the original with a precise duplicate. For now, the tiny image is behind glass, along with other reminders of that distant chase. His dark eyes look across a small space at the General, the engine that he hoped would help usher a quick end to what became a long war.

For more information, visit southernmuseum.org or call 770-427-2117.

April 14, 1962 The Little General is

brought back to Kennesaw

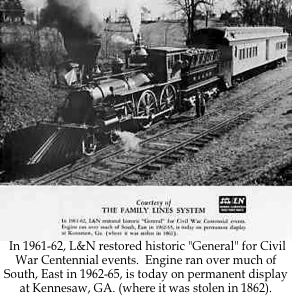

For more than 60 years the General had been a centerpiece of the Union Depot in Chattanooga. In June, 1961, the Louisville & Nashville moved her under cover of darkness from Chattanooga to Nashville. It was not the 1st time or last that a city suffered "General-envy." Stone Mountain, Atlanta, Marietta, Chickamauga battlefield, & Paterson (NJ) had expressed various levels of interest in the locomotive or actually made an attempt to take her.

Nashville's theft of the engine, tho, was well intentioned. The

L&N rebuilt The General to exhibit her for the Civil War

Centennial. On a cool February day in 1962 she came out

of her stall & moved under her own power for the 1st time

in more than 50 years. After returning to Louisville as the

Centennial ended the debate arose as to who should have the

General. The state of GA expressed an interest, but 60 years

in Union Station gave Chattanooga the rights to the locomotive.

Or so they thought.