SIGNIFICANCE/ANALYSIS

Following the Civil War and the national economic depression of 1873 to 1879, prosperity began a slow return to the South in general and the Atlanta area in particular. Of great importance in this prosperity was the International Cotton Exposition in 1881 in Atlanta, the first grand exposition held in the South. As historian Alice Galenson has noted, "The surge of interest in industrial endeavor in the South was manifested in the Atlanta Cotton Exposition of 1881, often credited with having inaugurated the cotton mill boom." For the next four decades, the three southern states of Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina experienced a tremendous growth in the construction of cotton mills, drawing on both local and New England capital and the exploitation of a large supply of cheap labor in the form of poor, mountain and/or rural whites. Whittier Mill and its surrounding village was established in 1895 and is a prime example of this early development of the southern mill and attached village. Its subsequent history illustrates the rise and decline of the textile industry in the South as well as the shift in industry and business from the older, industrial centers of the North and Northeast to the "Sunbelt". Although only a few remnants of the actual mill itself remain, the housing built for "operatives" stands largely intact, providing a good idea of life in a typical mill village of turn-of-the-century Atlanta.

HISTORY

The story of the textile industry in Georgia began before the Civil War. In fact, the state was the South's leader in textile plants in 1840 with nineteen factories located primarily in Augusta and Columbus. By 1848 there were thirty-two mills and by 1851, $1,000,000 had been invested in Georgia textile mills. Nevertheless, as Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. states in The Rise of the City, "Only a feeble start had been made at cotton manufacturing before 1878."

Eighteen-eighty was a crucial year for Atlanta and the South as a whole in regard to economic rejuvenation. Alice Galenson states that the loss of the presidency in that year by the Democratic Party made Southerners realize that the road to rehabilitation lay not in politics, but in developing a strong and viable economy. After the end of the 1870s depression and with the great expansion of railroad building in the South beginning around 1880, Atlanta and the region became more and more tied to a national economy through the rail networks. This helped spur the growth of an "active, self-conscious urban-commercial elite. . . ." (Blaine Brownell and David Goldfield in The City in Southern City, p. 14)

This "urban-commercial elite" proved particularly adept and successful in Atlanta and this success is best reflected in the International Cotton Exposition of 1881. As the South's first world's fair, it ". . . put Atlanta on the map as the headquarters of the New South movement . . .," a fact that urban boosters like Henry Grady would let no one forget. Arthur Schlesinger calls the result of the fair a drive for textile mills "akin to a religious fervor" which proved to be very successful. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the Piedmont fall line in the Carolinas and Georgia became heavily built up with the number of spindles and looms trebling and with the South developing a virtual monopoly in the United States production of coarse cotton cloth. Between 1880 and 1910, the average annual growth for southern textile production was 10 percent. In the three years from 1880 to 1884, Georgia spindles increased from 201,000 to 340,000 and looms from 4,713 to 7,843 according to the Manufacturers' Record as reported in the Atlanta Constitution for January 10, 1884. These figures made Georgia the leading southern textile state and caused the Constitution's editorial writers to state triumphantly:

And the bare fact that there is no lessening of the work of construction in the south during these days of depression, when northern mills are either reducing wages or shutting down, or passing into the hands of receivers, is sufficient evidence that southern mills have a margin of profit in even the hardest of times, and that mills will continue to be multiplied in the south until the bulk of cotton manufacturing is done where the plant is grown. (January 10, 1884)

Five years later in February 1890, the Atlanta Journal would gloat in a similar vein about the growing predominance of the South in textiles by stating editorially:

We once heard Rev. Henry Ward Beecher say in a so-called sermon before the war, 'every cotton mill established at the north would drive a nail into the coffin of slavery.' The abolition of slavery having led to a great increase in cotton manufacture in the south, there is now a likelihood that the nails are to be driven into the coffins of the mills of the north.

By the 1920s, the three states of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia formed the leading textile area in the nation and it is estimated that in that decade three-fourths of the United States' production was within twenty-four hours by rail of Atlanta. By 1889 textiles was first in Georgia in value added by industry and textile workers made up about a third of all manufacturing workers in the state from 1889 to 1929. New England had indeed been surpassed. The reasons for this supremacy are several. Labor was cheaper because northern mills relied heavily on immigrants who were usually predominantly male and were generally paid higher wages than women and children, the latter of whom made up almost a quarter of the southern textile labor force prior to 1900. Southern cities and states allowed longer work hours per week and often gave new mills lower taxes or complete tax exemptions in some cases. The Georgia Power Company could proudly state in 1920 in regard to textiles that ". . . no proposed measure, aimed against manufacture, ever has been given even serious consideration in the state." Also during this period, capital increased as northern and southern investors found that they could make more money in southern textiles mills than in their northern counterparts.

Finally, the southern wage scale was twenty-five to forty percent lower than in northern states. Although other factors were involved (such as water power), one of the prime reasons that so many mills were found in the Piedmont and Appalachian foothills was the higher percentage of white population there than in coastal areas. Since their only alternative was poverty stricken agricultural labor in direct competition with African-Americans (who were paid even less for their labor than whites), poor whites had little choice but to accept long hours, low wages, child labor, and paternalistic management. In a searing indictment of the situation, The Industrial Revolution in the South, written in 1930 by Broadus and George Mitchell, concluded:

The Poor Whites . . . by whose labor the industry has been built up, are now looked upon as a resource to be exploited. Not only is this true within the section, but the Poor Whites are being served up to employers . . . on the auction block pretty much as their black predecessors were . . . .

In a promotional pamphlet published in 1920 by Georgia Power to attract textile investment, the plenitude of native American, white labor was stressed and manufacturers moving to the South were counselled to "bring none of their foreign labor with them . . . ." Furthermore, it was pointed out that southern mills were operated "exclusively" by native born, white people since no foreign mill laborers have or ever will be invited to the region. "If there is one attraction stronger than all others, in north Georgia's field for cotton manufacture, it is the fact that there is a great reservoir of native-born American white labor of the old new England type." In addition, southern labor needed less meat to eat, less clothing, less heat and fuel, and less elaborate housing since most of it could be heated by fireplaces only. (Industrial Georgia, 1920)

Despite these conditions, it has been pointed that there were many advantages to living in the mill villages. Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. states that the new opportunities for human fellowship drew many mountain folk out of their lonely and desolate coves and valleys. Marvin Fischbaum concludes in An Economic Analysis of the Southern Capture of the Cotton Textile Industry Processing to 1910 that even with low wages and long hours, the former farmers did improve their economic conditions by becoming mill operatives since "Life in the rural South had been neither pleasant nor stimulating."

In a 1937 promotional pamphlet titled "Let's Keep the Cotton Mills in Georgia," the authors cited the lack of labor troubles because of the "intimate, friendly relationship between mill management and the mill workers. . . ." This attitude was responsible in great part for the settlement house movement in southern mill villages. Based on the example of such organizations as Jane Addams' Hull House in Chicago, settlement houses sought to alleviate some of the worst evils of industrialization and to improve the general standard of living. The most well known settlement house in Atlanta was that operated by the Methodist Church for Fulton Bag and Cotton. Given space and financial support by the mill owners, the Wesley Settlement House provided clubs and athletic games for children, a night school, a day care/nursery, medical clinics, a bathtub, and "bazaars" for purchasing supplies at cost.

WHITTIER MILLS

Served by the Southern Railroad (several trains a day) and an electric streetcar line running every thirty minutes, the mill and its village nestled in a small valley near the Chattahoochee River. Construction began in May 1895 and was completed in less than a year at a total cost of $180,000. Less than a quarter mile away was the Chattahoochee Brick Company, and a March 6, 1895 letter from that firm's vice president G. W. Parrott outlined and confirmed the financial arrangement between his corporation and Whittier Cotton Mills. The brick company sold thirty acres along the river and their manager's existing brick cottage and would construct a 40,000 square foot cotton mill, warehouse, and a storehouse of "the very finest hard brick" as well as thirty frame cottages for the operatives. The mill owners would apply half of the equipment from their existing mills in Massachusetts and half would be new. Chattahoochee Brick received $2,500 in cash and $50,000 in stock.

The mill company was named after the Whittier family of Massachusetts, which had started the business in Lowell. The actual owners, however, were Paul Butler, son of Civil War general Benjamin Butler, and several other prominent capitalists. Nevertheless, the Whittier family provided the major officers, including president Helen Whittier and treasurer Nelson Whittier. According to newspaper reports, it was Helen Whittier who selected the site for the southern branch of the ten mill system and who officially threw the switch to open the factory in 1896. Miss Whittier had come to Atlanta prior to the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition and was obviously attracted to the area for the firm's southern expansion. Her nephew Walter R. B. Whittier was installed as the manager, a job he would retain until 1936.

A special feature in the Atlanta Journal in July 1896 (six months after the mill had been operating) was subtitled "Quite a community itself/The Operatives Colonized in Comfortable Cottages -- Built by Capitalists of New England." In a typical Victorian prose, the writer stated: "One of the most picturesque places in the vicinity of Atlanta is Whittier Mills. . . . The houses of the operatives are built around the brow of the hill in a semi-circular shape. . . [that] resembles a half-moon. . . . The greatest number of these houses face the mill and are built of the best material with terraced yards and plenty of green grass, some of the more thrifty of the occupants already having roses planted and growing. Altogether they present an appearance of thrift and care not usually seen among people of this class." Guarding over the workers was manager Walter "Boss" Whittier in a large, brick house named "Hedgerows" on a nearby hill, and superintendent W. H. Salmon, also living on the property. The homes of these two men were heated with steam from the plant.

Other than jobs, which started in 1896 at one dollar a day, the mill owners, over the years, provided a settlement house, store, a school building with space for church services, and a golf course. In the east half of the mill store were dry goods, groceries were located in the west half and the Chattahoochee post office occupied the northwest corner. Directly across Parrott Avenue from the company store what was and is known as the "ark" which housed the barber shop, a shoe shop, a pharmacy, and the men's showers.

Housing was rented from the mill and paid for by the room. Most units were duplexes and were built with locks on both sides of the doors to each room so the interiors could be easily reconfigured when families needed more space. At $.50 per room, $1.50 per week, or $6.00 per four week month, the price included all maintenance and utilities. The mill kept the houses painted and the grass cut, provided water and electricity, and made all plumbing and electrical repairs. The original houses had wells for water, but when there was a mill expansion in 1926, the new houses had running water. The 1926 housing is distinguished by less steeply pitched roofs than the original dwellings and was designed by the Boston architectural firm of Parsons and Wait. Paul and Sid Whittier (sons of W. R. B. Whittier) oversaw the construction, which was of "Common Southern Pine," fireplaces and chimneys of Chattahoochee brick, and sited on pier foundations. The streets were unpaved, but rear alleys helped provide good drainage and the lots were smaller for easier upkeep. To this day, the 1926 construction is still called "New Village" by long time area residents.

That some "outside" help was needed, however, is reflected in W. R. B. Whittier's 1910 request that the Atlanta Sheltering Arms Association of Day Nurseries set up a settlement in the village. In addition to the nursery, there were kindergarten classes, night school for adults, clubs for boys and girls, and mothers' meetings with a social worker. A physician held free clinics twice weekly, and a brass band was organized for the young men, who performed in a bandstand located north of Parrott Avenue. The settlement house was in a large, three story building at the southeast corner of Parrott and Whittier Avenues (based on the 1911 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map), but was dismantled in 1926 with the waning of the settlement house movement in the United States during that decade. Sections of the settlement house were used to construct other houses in the expansion of the village that year.

Despite the many amenities provided by the mill owners, life for the workers was not easy even if it was a step up from rural or mountain poverty. Sid Whittier, the last member of his family to run the business, showed why this was when he stated that even with the low pay, ". . . there were hundreds of people for every job and none of them had ever worked in a factory before." The 1900 census lists 635 people working at Whittier Cotton Mills including 211 weavers, 135 spinners, 60 spoolers, 48 dolphers, 29 carders, 23 speeders, and 20 drawers. Many of the dolphers, weavers, and spinners were children as young as seven or nine years. The failure of southern states like Georgia to pass compulsory school attendance laws made it possible to employ children and helped the southern mills to have profits of twenty to seventy-five percent while their counterparts in New England might be actually losing money. Another factor in such profits was long hours. During its first decades, Whittier Mills ran seven days a week with two shifts, midnight to noon and noon to midnight. Six day work weeks were standard. According to I. A. Newby in Plain Folk in the New South, mill villages were often plagued with alcoholism and violence partially as a result of the hard conditions. He recounts numerous incidents throughout the South and one from Whittier Mills in 1905 when two male youths who had been drinking assaulted two young girls on a public street. All were workers at the mill. This and other similar incidents undoubtedly brought about the establishment of the settlement house in 1910, but it is difficult to imagine how the workers could realistically be expected to take advantage of its programs when whole families worked such long hours.

These workers or operatives primarily produced cotton yarn, ranging in size from "twos," used for window cord, to "forties," the finest of cotton filaments. "Softbacks" for gloves and mittens, braiders' yarn, druggists' twine, and wrappings for hose were also manufactured. Mississippi delta cotton was used for thread and California cotton was used for yarn. Yarn-wrapped water hose used for firehoses was the mills' specialty. The use of cotton fiber to make flexible firehoses had been developed by Paul Butler and Nelson Whittier prior to 1895 and the business had a virtual monopoly on the production due to patents on the circular loom and twister machinery these two men had developed. It was this part of the Whittier Mills production which was moved to Georgia with the opening of the new southern branch.

Nevertheless, the mills' wares changed with the times. In 1914 experiments with "mineral wool" or asbestos were recorded and in the late 1920s blue denim was sold to the United States penitentiary in Atlanta. During World War II, the mills made cloth for sandbags for the federal government. At other times, Whittier Mills produced corduroy cloth, garden hosing, and even synthetic cloth. In September 1926 the trade journal Cotton reported that the Silver Lake Company had applied for a charter to produce cordage at Whittier Mills in what was now called the suburb of Chattahoochee. It was this expansion of the mill by 65,000 square feet which brought about the already mentioned addition to the mill housing.

The 1930s proved a particularly difficult time for Whittier Mills and its workers. The Whittiers had had a virtual monopoly on firehose yarn production in the South until the depression when Callaway Mills hired a key worker, who stated Sid Whittier, ". . . took a complete set of yarn samples and the 'know-how'" with him. Bibb Manufacturing later hired knowledgeable personnel from Callaway, and three southern mills began to compete for the lucrative firehose business. Again according to Sid Whittier, ". . . the last to pirate his way in had a cost advantage because he comes in with more modern machinery." To earn extra money during the Depression, millworkers cut pieces for Ideal American Jigsaw puzzles in the evenings.

The loss of the monopoly and the depression ended the mills' expansion. Permanent lay-offs and short-term strikes occurred at Whittier Mills, which had begun to lose money on its Georgia operation. In 1934, the year of the General Textile Strike throughout the country in which so many southern millworkers participated, "Boss" Whittier left the operation. J. J. Scott of Scottdale Mills near Decatur became general manager. Scott divided his time between his own mills and their competition at Whittier Mills in the town of Chattahoochee. Scott put the mill back into the black and in 1936 placed Hanford Sams in the manager's position of both his mills. Sams eventually became vice president of the Whittier Mills board of directors under president Scott, who had taken over that position from Sid Whittier in 1936.

During the 1940s, the new management and wartime contracts brought renewed economic stability to the mill and the village. The employees' newsletter, Whittier Mills & Silver Lake News, reported on the prowess of the company baseball team with detailed accounts of winning seasons, playing against Clarkdale Thread Mill and Celanese (of Rome), and in 1948, the construction of new bleachers for the fans. That year the Osborne family were the big stars: the father, "Tiny," was once a major league player for Chicago and Brooklyn in the National League; "Jeter," one of his seven children, played in the Southern League for the New Orleans Pelicans; and another son, "Bottles" played for Rochester (AAA ball) and Birmingham in the Southern Association. In 1949, the trolley from Atlanta, filled with free riders for the occasion, made its last run to Chattahoochee.

Major changes occurred, however, in the 1950s. In 1952 the City of Atlanta annexed Chattahoochee, an unincorporated township since its foundation. It was also in this decade that J. P. Stevens sold Whittier Mills to Scott Dale Industries. Shortly after the mills' sale in 1954, the new owners began selling the mill houses to the tenants starting at $2,000. Butler Way was extended to occupy the old baseball grounds and several of the houses were moved there to create more equitably sized lots.

By mid-1971, Whittier Mills has closed for good following a decade of increasing competition from cheap imports. Company officials cited the problem as ". . . the accelerating flood of imports from low wage countries into our textile market. Added to this problem is the shortage of textile workers in this area." Although it was reported at the time that low unemployment figures for Atlanta meant the workers would probably find new jobs quickly, newspaper reports later that year stated that still unemployed workers from Whittier Mills would be eligible for extended benefits from the federal government because job loss was deemed the result of unfair trade practices.

For the next two decades, the mill buildings went unused. Several were burned by arsonists in 1986 and the owners proposed to turn the site into a landfill in 1980. Over the protests of local residents, the remaining structures were demolished in 1988 by Victorian Artifacts, Inc., which valued the massive heart-of-pine timbers and the antique bricks. The original mill tower which housed offices and a water tank for fire protection still remains. Meanwhile, a small investment group began to renovate the area's housing for resale. A 1991 article in the Atlanta Journal/Constitution Homefinder section indicated that the renovation work had been successful with the old mill houses selling for up to $75,000. One of the "amenities" cited in the article was that residents were seeking historic status.

ARCHITECTURE

The architecture of Whittier Mill Village reflects the consistency of building type and materials generally found in mill villages. The materials used in the construction of the cottages included wood siding, brick foundation piers and brick chimneys. Porches and moderately steep pitched roofs are elements common to structures built in both the first phase (1895) of construction and in the second phase (1926).

The most prevalent building type in the first phase was a cottage with a moderately steep hipped roof, a porch that extended across the front facade and a symmetrical arrangement of a central door flanked by two windows. Another building type constructed during this phase featured a steep pyramidal roof with two gables and a shed roofed porch.

A third type of building was built in the first construction stage that differs substantially from the cottages previously discussed. Several triplex structures with single "saltbox" gables extending their entire width were constructed. Although the rectangular shape of the footprint and the lower roof pitch are unique in the district, the broad front porch and wood siding were consistent with other mill houses. Several of these triplexes have been moved from their original location to other sites within the district, and are now used as single family homes.

Although the second major phase of development by the mill did not occur until 1926 there were a number of new houses built in 1910. For the most part the structures were hipped roof cottages with projecting front gables, however, several bungalows with large front gables were also constructed.

Parsons and Wait Architects of Boston, MA designed the houses of the (1926) second phase of development. The hipped roof which has a long ridge line perpendicular to the street is slightly less steep than that of the 1895 cottages, however, the design of these structures is generally consistent with the 1895 cottages.

Two original residential structures in the district are not consistent with the mill houses. The houses at #1 Spring Circle (2985 Parrott Avenue) and #3 Spring Circle (2992 Layton Avenue) are two surviving of four original houses built for the Whittier family. The structure at #1 Spring Circle was constructed in 1900. Although somewhat larger than mill cottages, the house resembles these structures in materials and roof form. The four pane, hinged casement windows and elaborate brickwork on the chimney are elements unique to the house. The structure at #3 Spring Circle (1897) is a large, two story home with a projecting bay window on the second level. The house is more complex in design than any of the other structures in the district.

Two original commercial structures remain in the district. The structure at 1952 Whittier Avenue (1897) is a long, one story, wood structure that was used for commercial purposes by the mill. It has been converted into three rental units. The original Whittier Mill dry goods and grocery store, which was built in 1896, is a brick and wood clapboard structure located at 2932 Parrott Avenue.

CONCLUSION

Whittier Mill is a local reminder of a period of great importance to the history of Atlanta and the Southeast. As the "New South" emerged from the ruin and chaos of civil war and reconstruction, Atlanta became a regional symbol and center for economic rejuvenation. As the increasing railroads tied the Southeast to Atlanta, and both the region and the city to a national market economy, industries developed along the rail lines and near labor supplies. The mill villages provided a transitional area for rural and mountain people to adjust to communal and even urban life in some cases. Under the paternalistic, if hard and demanding, eye of the mill owners and managers, poor whites did indeed achieve a new lifestyle as the twentieth century dawned while enduring low wages, long hours and the utilization of child labor. The mills themselves also offered the change for interregional cooperation between southern and northern investors.

Whittier Village was connected early on by streetcar lines and a commuter railroad to the larger metropolis. Churches and schools were built to encourage socialization, education, and worker stability. The placement of the settlement house in the community in 1910 shows the prevalence of the Progressive Movement's ideas in Atlanta as it helped introduce modern medical treatment and group activities to the "villagers."

The large, community-oriented buildings of the mill and settlement house are unfortunately gone. The distinctive and typical mill tower (needed to contain a water tank for fire protection) remains to create a visual anchor for the industrial nature of the development, however. Most important, the housing of the workers or operatives remains and gives a true sense of time and place, especially if interpreted realistically. According to local residents, there has been very little new construction in the community since the 1920s, thus enhancing the value of Whittier Mill as an historic district.

Following the Civil War and the national economic depression of 1873 to 1879, prosperity began a slow return to the South in general and the Atlanta area in particular. Of great importance in this prosperity was the International Cotton Exposition in 1881 in Atlanta, the first grand exposition held in the South. As historian Alice Galenson has noted, "The surge of interest in industrial endeavor in the South was manifested in the Atlanta Cotton Exposition of 1881, often credited with having inaugurated the cotton mill boom." For the next four decades, the three southern states of Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina experienced a tremendous growth in the construction of cotton mills, drawing on both local and New England capital and the exploitation of a large supply of cheap labor in the form of poor, mountain and/or rural whites. Whittier Mill and its surrounding village was established in 1895 and is a prime example of this early development of the southern mill and attached village. Its subsequent history illustrates the rise and decline of the textile industry in the South as well as the shift in industry and business from the older, industrial centers of the North and Northeast to the "Sunbelt". Although only a few remnants of the actual mill itself remain, the housing built for "operatives" stands largely intact, providing a good idea of life in a typical mill village of turn-of-the-century Atlanta.

HISTORY

The story of the textile industry in Georgia began before the Civil War. In fact, the state was the South's leader in textile plants in 1840 with nineteen factories located primarily in Augusta and Columbus. By 1848 there were thirty-two mills and by 1851, $1,000,000 had been invested in Georgia textile mills. Nevertheless, as Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. states in The Rise of the City, "Only a feeble start had been made at cotton manufacturing before 1878."

Eighteen-eighty was a crucial year for Atlanta and the South as a whole in regard to economic rejuvenation. Alice Galenson states that the loss of the presidency in that year by the Democratic Party made Southerners realize that the road to rehabilitation lay not in politics, but in developing a strong and viable economy. After the end of the 1870s depression and with the great expansion of railroad building in the South beginning around 1880, Atlanta and the region became more and more tied to a national economy through the rail networks. This helped spur the growth of an "active, self-conscious urban-commercial elite. . . ." (Blaine Brownell and David Goldfield in The City in Southern City, p. 14)

This "urban-commercial elite" proved particularly adept and successful in Atlanta and this success is best reflected in the International Cotton Exposition of 1881. As the South's first world's fair, it ". . . put Atlanta on the map as the headquarters of the New South movement . . .," a fact that urban boosters like Henry Grady would let no one forget. Arthur Schlesinger calls the result of the fair a drive for textile mills "akin to a religious fervor" which proved to be very successful. During the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the Piedmont fall line in the Carolinas and Georgia became heavily built up with the number of spindles and looms trebling and with the South developing a virtual monopoly in the United States production of coarse cotton cloth. Between 1880 and 1910, the average annual growth for southern textile production was 10 percent. In the three years from 1880 to 1884, Georgia spindles increased from 201,000 to 340,000 and looms from 4,713 to 7,843 according to the Manufacturers' Record as reported in the Atlanta Constitution for January 10, 1884. These figures made Georgia the leading southern textile state and caused the Constitution's editorial writers to state triumphantly:

And the bare fact that there is no lessening of the work of construction in the south during these days of depression, when northern mills are either reducing wages or shutting down, or passing into the hands of receivers, is sufficient evidence that southern mills have a margin of profit in even the hardest of times, and that mills will continue to be multiplied in the south until the bulk of cotton manufacturing is done where the plant is grown. (January 10, 1884)

Five years later in February 1890, the Atlanta Journal would gloat in a similar vein about the growing predominance of the South in textiles by stating editorially:

We once heard Rev. Henry Ward Beecher say in a so-called sermon before the war, 'every cotton mill established at the north would drive a nail into the coffin of slavery.' The abolition of slavery having led to a great increase in cotton manufacture in the south, there is now a likelihood that the nails are to be driven into the coffins of the mills of the north.

By the 1920s, the three states of North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia formed the leading textile area in the nation and it is estimated that in that decade three-fourths of the United States' production was within twenty-four hours by rail of Atlanta. By 1889 textiles was first in Georgia in value added by industry and textile workers made up about a third of all manufacturing workers in the state from 1889 to 1929. New England had indeed been surpassed. The reasons for this supremacy are several. Labor was cheaper because northern mills relied heavily on immigrants who were usually predominantly male and were generally paid higher wages than women and children, the latter of whom made up almost a quarter of the southern textile labor force prior to 1900. Southern cities and states allowed longer work hours per week and often gave new mills lower taxes or complete tax exemptions in some cases. The Georgia Power Company could proudly state in 1920 in regard to textiles that ". . . no proposed measure, aimed against manufacture, ever has been given even serious consideration in the state." Also during this period, capital increased as northern and southern investors found that they could make more money in southern textiles mills than in their northern counterparts.

Finally, the southern wage scale was twenty-five to forty percent lower than in northern states. Although other factors were involved (such as water power), one of the prime reasons that so many mills were found in the Piedmont and Appalachian foothills was the higher percentage of white population there than in coastal areas. Since their only alternative was poverty stricken agricultural labor in direct competition with African-Americans (who were paid even less for their labor than whites), poor whites had little choice but to accept long hours, low wages, child labor, and paternalistic management. In a searing indictment of the situation, The Industrial Revolution in the South, written in 1930 by Broadus and George Mitchell, concluded:

The Poor Whites . . . by whose labor the industry has been built up, are now looked upon as a resource to be exploited. Not only is this true within the section, but the Poor Whites are being served up to employers . . . on the auction block pretty much as their black predecessors were . . . .

In a promotional pamphlet published in 1920 by Georgia Power to attract textile investment, the plenitude of native American, white labor was stressed and manufacturers moving to the South were counselled to "bring none of their foreign labor with them . . . ." Furthermore, it was pointed out that southern mills were operated "exclusively" by native born, white people since no foreign mill laborers have or ever will be invited to the region. "If there is one attraction stronger than all others, in north Georgia's field for cotton manufacture, it is the fact that there is a great reservoir of native-born American white labor of the old new England type." In addition, southern labor needed less meat to eat, less clothing, less heat and fuel, and less elaborate housing since most of it could be heated by fireplaces only. (Industrial Georgia, 1920)

Despite these conditions, it has been pointed that there were many advantages to living in the mill villages. Arthur Schlesinger, Sr. states that the new opportunities for human fellowship drew many mountain folk out of their lonely and desolate coves and valleys. Marvin Fischbaum concludes in An Economic Analysis of the Southern Capture of the Cotton Textile Industry Processing to 1910 that even with low wages and long hours, the former farmers did improve their economic conditions by becoming mill operatives since "Life in the rural South had been neither pleasant nor stimulating."

In a 1937 promotional pamphlet titled "Let's Keep the Cotton Mills in Georgia," the authors cited the lack of labor troubles because of the "intimate, friendly relationship between mill management and the mill workers. . . ." This attitude was responsible in great part for the settlement house movement in southern mill villages. Based on the example of such organizations as Jane Addams' Hull House in Chicago, settlement houses sought to alleviate some of the worst evils of industrialization and to improve the general standard of living. The most well known settlement house in Atlanta was that operated by the Methodist Church for Fulton Bag and Cotton. Given space and financial support by the mill owners, the Wesley Settlement House provided clubs and athletic games for children, a night school, a day care/nursery, medical clinics, a bathtub, and "bazaars" for purchasing supplies at cost.

WHITTIER MILLS

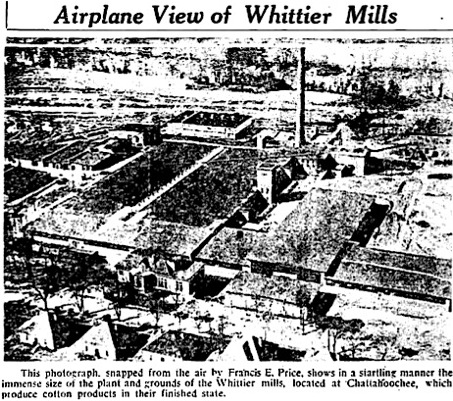

Served by the Southern Railroad (several trains a day) and an electric streetcar line running every thirty minutes, the mill and its village nestled in a small valley near the Chattahoochee River. Construction began in May 1895 and was completed in less than a year at a total cost of $180,000. Less than a quarter mile away was the Chattahoochee Brick Company, and a March 6, 1895 letter from that firm's vice president G. W. Parrott outlined and confirmed the financial arrangement between his corporation and Whittier Cotton Mills. The brick company sold thirty acres along the river and their manager's existing brick cottage and would construct a 40,000 square foot cotton mill, warehouse, and a storehouse of "the very finest hard brick" as well as thirty frame cottages for the operatives. The mill owners would apply half of the equipment from their existing mills in Massachusetts and half would be new. Chattahoochee Brick received $2,500 in cash and $50,000 in stock.

The mill company was named after the Whittier family of Massachusetts, which had started the business in Lowell. The actual owners, however, were Paul Butler, son of Civil War general Benjamin Butler, and several other prominent capitalists. Nevertheless, the Whittier family provided the major officers, including president Helen Whittier and treasurer Nelson Whittier. According to newspaper reports, it was Helen Whittier who selected the site for the southern branch of the ten mill system and who officially threw the switch to open the factory in 1896. Miss Whittier had come to Atlanta prior to the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition and was obviously attracted to the area for the firm's southern expansion. Her nephew Walter R. B. Whittier was installed as the manager, a job he would retain until 1936.

A special feature in the Atlanta Journal in July 1896 (six months after the mill had been operating) was subtitled "Quite a community itself/The Operatives Colonized in Comfortable Cottages -- Built by Capitalists of New England." In a typical Victorian prose, the writer stated: "One of the most picturesque places in the vicinity of Atlanta is Whittier Mills. . . . The houses of the operatives are built around the brow of the hill in a semi-circular shape. . . [that] resembles a half-moon. . . . The greatest number of these houses face the mill and are built of the best material with terraced yards and plenty of green grass, some of the more thrifty of the occupants already having roses planted and growing. Altogether they present an appearance of thrift and care not usually seen among people of this class." Guarding over the workers was manager Walter "Boss" Whittier in a large, brick house named "Hedgerows" on a nearby hill, and superintendent W. H. Salmon, also living on the property. The homes of these two men were heated with steam from the plant.

Other than jobs, which started in 1896 at one dollar a day, the mill owners, over the years, provided a settlement house, store, a school building with space for church services, and a golf course. In the east half of the mill store were dry goods, groceries were located in the west half and the Chattahoochee post office occupied the northwest corner. Directly across Parrott Avenue from the company store what was and is known as the "ark" which housed the barber shop, a shoe shop, a pharmacy, and the men's showers.

Housing was rented from the mill and paid for by the room. Most units were duplexes and were built with locks on both sides of the doors to each room so the interiors could be easily reconfigured when families needed more space. At $.50 per room, $1.50 per week, or $6.00 per four week month, the price included all maintenance and utilities. The mill kept the houses painted and the grass cut, provided water and electricity, and made all plumbing and electrical repairs. The original houses had wells for water, but when there was a mill expansion in 1926, the new houses had running water. The 1926 housing is distinguished by less steeply pitched roofs than the original dwellings and was designed by the Boston architectural firm of Parsons and Wait. Paul and Sid Whittier (sons of W. R. B. Whittier) oversaw the construction, which was of "Common Southern Pine," fireplaces and chimneys of Chattahoochee brick, and sited on pier foundations. The streets were unpaved, but rear alleys helped provide good drainage and the lots were smaller for easier upkeep. To this day, the 1926 construction is still called "New Village" by long time area residents.

That some "outside" help was needed, however, is reflected in W. R. B. Whittier's 1910 request that the Atlanta Sheltering Arms Association of Day Nurseries set up a settlement in the village. In addition to the nursery, there were kindergarten classes, night school for adults, clubs for boys and girls, and mothers' meetings with a social worker. A physician held free clinics twice weekly, and a brass band was organized for the young men, who performed in a bandstand located north of Parrott Avenue. The settlement house was in a large, three story building at the southeast corner of Parrott and Whittier Avenues (based on the 1911 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map), but was dismantled in 1926 with the waning of the settlement house movement in the United States during that decade. Sections of the settlement house were used to construct other houses in the expansion of the village that year.

Despite the many amenities provided by the mill owners, life for the workers was not easy even if it was a step up from rural or mountain poverty. Sid Whittier, the last member of his family to run the business, showed why this was when he stated that even with the low pay, ". . . there were hundreds of people for every job and none of them had ever worked in a factory before." The 1900 census lists 635 people working at Whittier Cotton Mills including 211 weavers, 135 spinners, 60 spoolers, 48 dolphers, 29 carders, 23 speeders, and 20 drawers. Many of the dolphers, weavers, and spinners were children as young as seven or nine years. The failure of southern states like Georgia to pass compulsory school attendance laws made it possible to employ children and helped the southern mills to have profits of twenty to seventy-five percent while their counterparts in New England might be actually losing money. Another factor in such profits was long hours. During its first decades, Whittier Mills ran seven days a week with two shifts, midnight to noon and noon to midnight. Six day work weeks were standard. According to I. A. Newby in Plain Folk in the New South, mill villages were often plagued with alcoholism and violence partially as a result of the hard conditions. He recounts numerous incidents throughout the South and one from Whittier Mills in 1905 when two male youths who had been drinking assaulted two young girls on a public street. All were workers at the mill. This and other similar incidents undoubtedly brought about the establishment of the settlement house in 1910, but it is difficult to imagine how the workers could realistically be expected to take advantage of its programs when whole families worked such long hours.

These workers or operatives primarily produced cotton yarn, ranging in size from "twos," used for window cord, to "forties," the finest of cotton filaments. "Softbacks" for gloves and mittens, braiders' yarn, druggists' twine, and wrappings for hose were also manufactured. Mississippi delta cotton was used for thread and California cotton was used for yarn. Yarn-wrapped water hose used for firehoses was the mills' specialty. The use of cotton fiber to make flexible firehoses had been developed by Paul Butler and Nelson Whittier prior to 1895 and the business had a virtual monopoly on the production due to patents on the circular loom and twister machinery these two men had developed. It was this part of the Whittier Mills production which was moved to Georgia with the opening of the new southern branch.

Nevertheless, the mills' wares changed with the times. In 1914 experiments with "mineral wool" or asbestos were recorded and in the late 1920s blue denim was sold to the United States penitentiary in Atlanta. During World War II, the mills made cloth for sandbags for the federal government. At other times, Whittier Mills produced corduroy cloth, garden hosing, and even synthetic cloth. In September 1926 the trade journal Cotton reported that the Silver Lake Company had applied for a charter to produce cordage at Whittier Mills in what was now called the suburb of Chattahoochee. It was this expansion of the mill by 65,000 square feet which brought about the already mentioned addition to the mill housing.

The 1930s proved a particularly difficult time for Whittier Mills and its workers. The Whittiers had had a virtual monopoly on firehose yarn production in the South until the depression when Callaway Mills hired a key worker, who stated Sid Whittier, ". . . took a complete set of yarn samples and the 'know-how'" with him. Bibb Manufacturing later hired knowledgeable personnel from Callaway, and three southern mills began to compete for the lucrative firehose business. Again according to Sid Whittier, ". . . the last to pirate his way in had a cost advantage because he comes in with more modern machinery." To earn extra money during the Depression, millworkers cut pieces for Ideal American Jigsaw puzzles in the evenings.

The loss of the monopoly and the depression ended the mills' expansion. Permanent lay-offs and short-term strikes occurred at Whittier Mills, which had begun to lose money on its Georgia operation. In 1934, the year of the General Textile Strike throughout the country in which so many southern millworkers participated, "Boss" Whittier left the operation. J. J. Scott of Scottdale Mills near Decatur became general manager. Scott divided his time between his own mills and their competition at Whittier Mills in the town of Chattahoochee. Scott put the mill back into the black and in 1936 placed Hanford Sams in the manager's position of both his mills. Sams eventually became vice president of the Whittier Mills board of directors under president Scott, who had taken over that position from Sid Whittier in 1936.

During the 1940s, the new management and wartime contracts brought renewed economic stability to the mill and the village. The employees' newsletter, Whittier Mills & Silver Lake News, reported on the prowess of the company baseball team with detailed accounts of winning seasons, playing against Clarkdale Thread Mill and Celanese (of Rome), and in 1948, the construction of new bleachers for the fans. That year the Osborne family were the big stars: the father, "Tiny," was once a major league player for Chicago and Brooklyn in the National League; "Jeter," one of his seven children, played in the Southern League for the New Orleans Pelicans; and another son, "Bottles" played for Rochester (AAA ball) and Birmingham in the Southern Association. In 1949, the trolley from Atlanta, filled with free riders for the occasion, made its last run to Chattahoochee.

Major changes occurred, however, in the 1950s. In 1952 the City of Atlanta annexed Chattahoochee, an unincorporated township since its foundation. It was also in this decade that J. P. Stevens sold Whittier Mills to Scott Dale Industries. Shortly after the mills' sale in 1954, the new owners began selling the mill houses to the tenants starting at $2,000. Butler Way was extended to occupy the old baseball grounds and several of the houses were moved there to create more equitably sized lots.

By mid-1971, Whittier Mills has closed for good following a decade of increasing competition from cheap imports. Company officials cited the problem as ". . . the accelerating flood of imports from low wage countries into our textile market. Added to this problem is the shortage of textile workers in this area." Although it was reported at the time that low unemployment figures for Atlanta meant the workers would probably find new jobs quickly, newspaper reports later that year stated that still unemployed workers from Whittier Mills would be eligible for extended benefits from the federal government because job loss was deemed the result of unfair trade practices.

For the next two decades, the mill buildings went unused. Several were burned by arsonists in 1986 and the owners proposed to turn the site into a landfill in 1980. Over the protests of local residents, the remaining structures were demolished in 1988 by Victorian Artifacts, Inc., which valued the massive heart-of-pine timbers and the antique bricks. The original mill tower which housed offices and a water tank for fire protection still remains. Meanwhile, a small investment group began to renovate the area's housing for resale. A 1991 article in the Atlanta Journal/Constitution Homefinder section indicated that the renovation work had been successful with the old mill houses selling for up to $75,000. One of the "amenities" cited in the article was that residents were seeking historic status.

ARCHITECTURE

The architecture of Whittier Mill Village reflects the consistency of building type and materials generally found in mill villages. The materials used in the construction of the cottages included wood siding, brick foundation piers and brick chimneys. Porches and moderately steep pitched roofs are elements common to structures built in both the first phase (1895) of construction and in the second phase (1926).

The most prevalent building type in the first phase was a cottage with a moderately steep hipped roof, a porch that extended across the front facade and a symmetrical arrangement of a central door flanked by two windows. Another building type constructed during this phase featured a steep pyramidal roof with two gables and a shed roofed porch.

A third type of building was built in the first construction stage that differs substantially from the cottages previously discussed. Several triplex structures with single "saltbox" gables extending their entire width were constructed. Although the rectangular shape of the footprint and the lower roof pitch are unique in the district, the broad front porch and wood siding were consistent with other mill houses. Several of these triplexes have been moved from their original location to other sites within the district, and are now used as single family homes.

Although the second major phase of development by the mill did not occur until 1926 there were a number of new houses built in 1910. For the most part the structures were hipped roof cottages with projecting front gables, however, several bungalows with large front gables were also constructed.

Parsons and Wait Architects of Boston, MA designed the houses of the (1926) second phase of development. The hipped roof which has a long ridge line perpendicular to the street is slightly less steep than that of the 1895 cottages, however, the design of these structures is generally consistent with the 1895 cottages.

Two original residential structures in the district are not consistent with the mill houses. The houses at #1 Spring Circle (2985 Parrott Avenue) and #3 Spring Circle (2992 Layton Avenue) are two surviving of four original houses built for the Whittier family. The structure at #1 Spring Circle was constructed in 1900. Although somewhat larger than mill cottages, the house resembles these structures in materials and roof form. The four pane, hinged casement windows and elaborate brickwork on the chimney are elements unique to the house. The structure at #3 Spring Circle (1897) is a large, two story home with a projecting bay window on the second level. The house is more complex in design than any of the other structures in the district.

Two original commercial structures remain in the district. The structure at 1952 Whittier Avenue (1897) is a long, one story, wood structure that was used for commercial purposes by the mill. It has been converted into three rental units. The original Whittier Mill dry goods and grocery store, which was built in 1896, is a brick and wood clapboard structure located at 2932 Parrott Avenue.

CONCLUSION

Whittier Mill is a local reminder of a period of great importance to the history of Atlanta and the Southeast. As the "New South" emerged from the ruin and chaos of civil war and reconstruction, Atlanta became a regional symbol and center for economic rejuvenation. As the increasing railroads tied the Southeast to Atlanta, and both the region and the city to a national market economy, industries developed along the rail lines and near labor supplies. The mill villages provided a transitional area for rural and mountain people to adjust to communal and even urban life in some cases. Under the paternalistic, if hard and demanding, eye of the mill owners and managers, poor whites did indeed achieve a new lifestyle as the twentieth century dawned while enduring low wages, long hours and the utilization of child labor. The mills themselves also offered the change for interregional cooperation between southern and northern investors.

Whittier Village was connected early on by streetcar lines and a commuter railroad to the larger metropolis. Churches and schools were built to encourage socialization, education, and worker stability. The placement of the settlement house in the community in 1910 shows the prevalence of the Progressive Movement's ideas in Atlanta as it helped introduce modern medical treatment and group activities to the "villagers."

The large, community-oriented buildings of the mill and settlement house are unfortunately gone. The distinctive and typical mill tower (needed to contain a water tank for fire protection) remains to create a visual anchor for the industrial nature of the development, however. Most important, the housing of the workers or operatives remains and gives a true sense of time and place, especially if interpreted realistically. According to local residents, there has been very little new construction in the community since the 1920s, thus enhancing the value of Whittier Mill as an historic district.

Whittier Mill Village is a Historic District in the City of Atlanta. Nestled along the Chattahoochee River, the former cotton mill site is now a 17 acre city park. The surrounding mill village is a lovely neighborhood of restored homes and cottages with a few newer homes built to Historical Architectural Guide lines.

May 1, 1927

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Proposed Designation: Historic District

October 28, 1994

District 17, Land Lots 263 and 256

Fulton County, City of Atlanta

Existing Zoning R5, I2

BOUNDARIES

Subarea 1 (Residential) of the proposed district includes properties fronting on the east and west sides of Whittier Avenue from Wales Avenue on the north to Maco Street on the south; also properties fronting on the north side of Maco Street from the west property line of 2933 Maco Street on the west to the east property line of 2884 Macaw Street on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Macaw Street from the west property lines of 2930 Macaw Street (south side) and 2931 Macaw Street (north side) on the west to the east property lines of 2884 Macaw Street (south side) and 2885 Macaw Street (north side) on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Parrot Avenue from the west property lines of 2946 Parrot Avenue (south side) and 2985 Parrot Avenue (north side) on the west to the east property lines of 2898 Parrot Avenue (south side) and 2869 Parrot Avenue (north side) on the east; also that property 1970 Tribble Avenue, fronting 140.8 feet on the west side of Tribble Avenue; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Layton Avenue from the west property lines of 2992 Layton Avenue (south side) and 2991 Layton Avenue (north side) on the west to Butler Way on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Burden Street from Butler Way on the west to the east property lines of 2867 Burden Street (north side) and 2868 Burden Street (south side) on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Fabin Street from Butler Way on the west to the east property lines of 2870 Fabin Street (south side) and 2875 Fabin Street (north side) on the east; also the property at 2943 Wales Avenue, fronting 70 feet on the north side of Wales Avenue; also properties fronting on the east and west sides of Butler Way from Parrot Avenue on the south to the north property lines of 2082 Butler Way (west side) and 2083 Butler Way (east side) on the north; also properties fronting on the east side of Spad Avenue from Layton Street on the south to the north property line of 2001 Spad Avenue on the north. Subarea II (Transitional) of the proposed district includes that property at 2085 Butler Way, fronting 50 feet on the dead end of Butler Way.

Proposed Designation: Historic District

October 28, 1994

District 17, Land Lots 263 and 256

Fulton County, City of Atlanta

Existing Zoning R5, I2

BOUNDARIES

Subarea 1 (Residential) of the proposed district includes properties fronting on the east and west sides of Whittier Avenue from Wales Avenue on the north to Maco Street on the south; also properties fronting on the north side of Maco Street from the west property line of 2933 Maco Street on the west to the east property line of 2884 Macaw Street on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Macaw Street from the west property lines of 2930 Macaw Street (south side) and 2931 Macaw Street (north side) on the west to the east property lines of 2884 Macaw Street (south side) and 2885 Macaw Street (north side) on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Parrot Avenue from the west property lines of 2946 Parrot Avenue (south side) and 2985 Parrot Avenue (north side) on the west to the east property lines of 2898 Parrot Avenue (south side) and 2869 Parrot Avenue (north side) on the east; also that property 1970 Tribble Avenue, fronting 140.8 feet on the west side of Tribble Avenue; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Layton Avenue from the west property lines of 2992 Layton Avenue (south side) and 2991 Layton Avenue (north side) on the west to Butler Way on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Burden Street from Butler Way on the west to the east property lines of 2867 Burden Street (north side) and 2868 Burden Street (south side) on the east; also properties fronting on the north and south sides of Fabin Street from Butler Way on the west to the east property lines of 2870 Fabin Street (south side) and 2875 Fabin Street (north side) on the east; also the property at 2943 Wales Avenue, fronting 70 feet on the north side of Wales Avenue; also properties fronting on the east and west sides of Butler Way from Parrot Avenue on the south to the north property lines of 2082 Butler Way (west side) and 2083 Butler Way (east side) on the north; also properties fronting on the east side of Spad Avenue from Layton Street on the south to the north property line of 2001 Spad Avenue on the north. Subarea II (Transitional) of the proposed district includes that property at 2085 Butler Way, fronting 50 feet on the dead end of Butler Way.

lat:3348652N

long:08429028W

W.Mill Park

is located at

Spad Ave. and

Wales Ave.

It is 22 acres